from 10/02/95, for AML 3124

Every artistic creation can be classified into a genre. As restaurants are categorized by the food they serve – French, Italian, Japanese, “fast food”, “pub grub” – so are literary works categorized by the styles in which they are written – essay, novel, short story, autobiography. These categorizations are as important to readers as they are to diners. It would be quite a surprise to enter an eatery called “Luigi’s Pizza” and discover the main fare was Peking Duck. What courses of action would be available? What if “Luigi’s” was the only restaurant for miles? What if “Luigi’s” was someone else’s choice, a sort of “required eating” for a dinner? Literary genres make reading easier by providing a stable ground upon which well-established styles are built.

An autobiography is an account of a life written by the one who has led it. It is one of a very few literary forms which are held to be immutable. A writer who recounts the events of another person’s life has the freedom to do so in almost any way imaginable. A poet has an infinite multitude of options when creating poetry – rhyming, meter, tense, even spelling are all transformable at the poet’s discretion. A public speaker has several forms of rhetoric with which to present an idea. Novels have limitless possibilities for an author to explore. But an autobiography must be a factual account of the life, or details of the life, of the writer who is writing one. When one is presented an autobiography it is immediately known that the author has written from first-hand, self-knowledge of the events described. It is an accepted fact that an autobiography is written in the first person and is not fiction.

The short story genre, although not as constrained as the autobiography, also has predetermined guidelines. Length is obviously a factor. A short story is written like a meal’s appetizer is prepared – in an easily digestible, bite-sized form designed to evoke one feeling from its reader. A short story is also generally expected to be fiction. When one is presented a short story it is immediately known that the author has created an experience with a beginning, middle, and end that can stand alone as a simplified expression of a larger theme.

Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and Ernest Hemingway’s collection of short stories In Our Time both present difficulties for the reader. By misrepresenting their respective genres, they confuse a reader and force themselves to be accepted in different ways. Both works disable the control mechanisms of readers and in doing so make it nearly impossible to carry preconceived notions while reading them. They must be read with an open understanding that they are not to be easily understood. They dictate the understanding allowed to the reader as they progress and when completed the reader must make conclusions based solely on the living text which has been absorbed.

Because The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas was not, in fact, authored by Alice B. Toklas, the reader is automatically doubtful of the validity of its content. Its very title is an untruth, and an untruth which, by its very nature, undermines all of a reader’s preconceived expectations of an autobiography. And yet after only a few pages it is clear that the book is not fiction. What it is, though, is not at first clear. After realizing that specific events are detailed which could not have been experienced by Alice B. Toklas (e.g. Gertrude Stein’s time in Paris before Toklas arrived there, conversations Stein had outside of Toklas’ presence) the reader must acknowledge that she is not the true author of the work. But how can one not be the author of one’s own autobiography? By enveloping herself in Toklas’ persona, Stein simultaneously absolves herself of the responsibilities of her writing and frees herself to be as honest and scathing, or generous and complimentary, as she wishes.

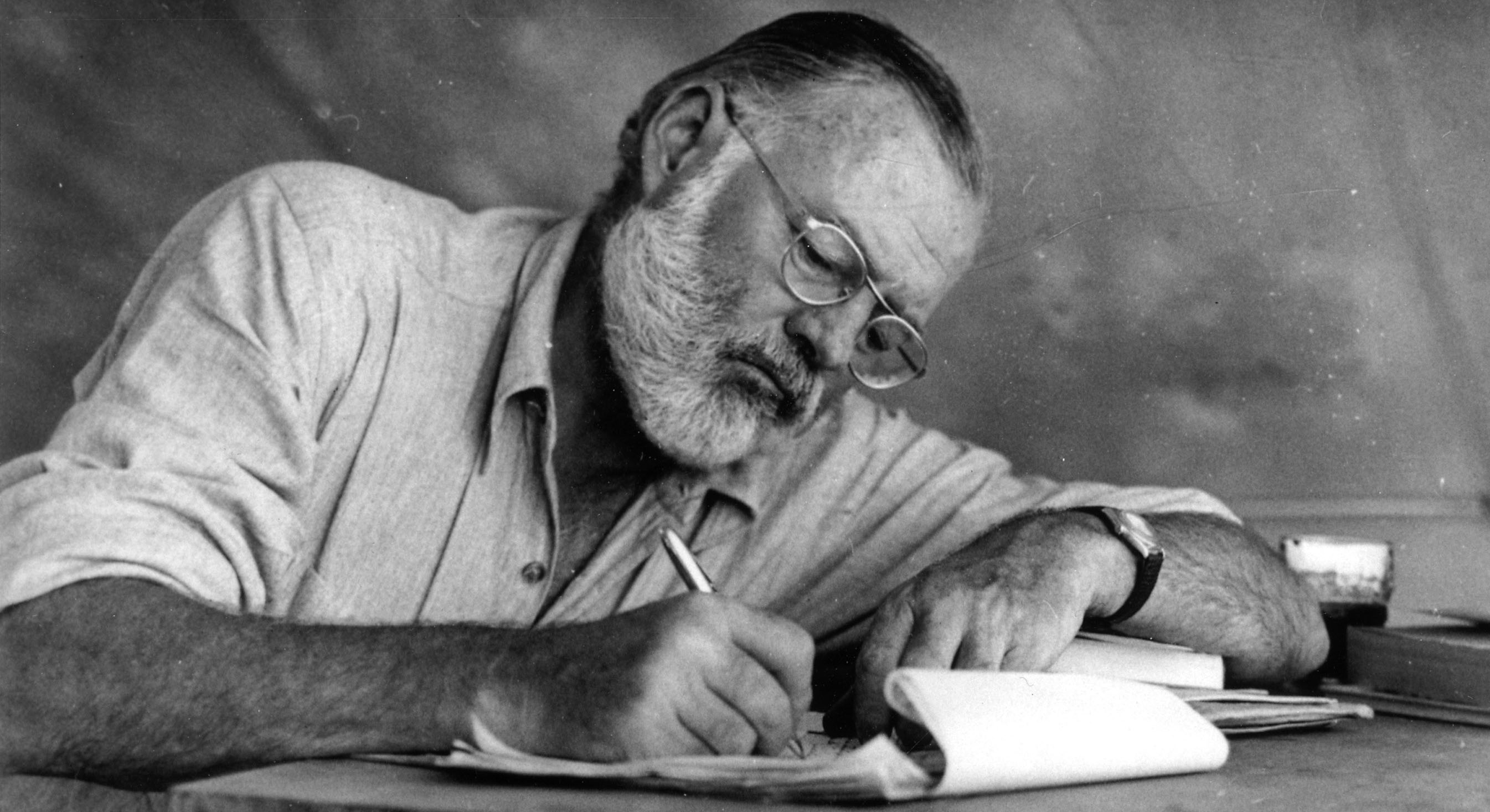

Ernest Hemingway’s collection of short stories In Our Time is an example of the author’s exploration of new territory in the genre. Although Hemingway’s selections can be seen as “short stories” in the traditional sense, to do so is to do them injustice. They are not traditional short stories in the same way that The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is not an autobiography. Starting with the first piece, “On the Quai at Smyrna”, the reader is carried through a cornucopia of creatively crafted characterizations of a conscience embroiled in the turmoil of war. The first World War manifests itself as not only military imagery but also the battles of love (“The End of Something”), friendship (“Cross-Country Snow”), birth and death (“Indian Camp” and “My Old Man”), and sport (“Big Two-Hearted River: Parts I and II”). The short stories do not always have clearly delineated beginnings, middles, and endings, and although they do not all tell a continuous tale, they seem to be connected in some deeper way which is perhaps not even meant to be understood by the reader. This is a departure from “the generic expectations of the genre.”

Short stories are supposed to stand alone, and the stories of In Our Time seem to depend upon each other in an inexplicable way. It is this semi-connectedness which has always been a problem for readers of the work. Interrupting the short stories are vignettes titled as “Chapters” which also confuse the fluidity of In Our Time. They are blatantly connected to each other and the short stories but they are too short to explain themselves; they can only titillate the reader’s taste buds with an emotion and then they are gone, leaving only the ephemeral feeling that something is being deeply explored without an explanation of what that something could be. Hemingway is able to occasionally, through these vignettes, shock the reader into a state of unsurety and then bring that reader back to the still-uncomfortable rendering of his battles.

Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway were both able to take a literary form and transform it into a vehicle for communicating an understanding for themselves. They both are seen now as avant-garde writers who dramatically influenced western literature. Although pizza was expected, the Peking Duck tasted delicious. By misrepresenting the genres in which they wrote, Stein and Hemingway were able to express themselves more freely.